Featured

- Get link

- X

- Other Apps

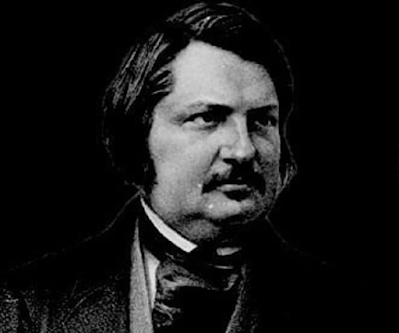

Honoré de Balzac

In 1799, an aspirant bourgeois family gave birth to Honoré Balzac in Tours, France.

Later, the family gave him the title Honoré de Balzac and claimed noble descent.

The renowned novelist passed away in Paris in 1850 after penning over 90 novels as well as several plays, essays, and short tales.

In his works, Balzac avoided using the adjective "dandy." In the 1830s and 1840s, it was associated with English eccentricity and foppishness in France.

"In making oneself a dandy, a man becomes a piece of boudoir furniture, an exceptionally intelligent man-nequin, who may sit upon a horse or a couch," he said in his Traité de la vie élégante (Treatise on the Elegant Life) of 1830.

nonetheless, a thinking being never.

Despite his criticisms of the dandy's intelligence, he was a huge fan of British tailoring and manly grace.

Henry de Marsay, one of his most well-known literary dandies, personifies the sexual allure and ambiguity of Balzac's interpretation of the dandy.

De Marsay was "renowned for the feelings he provoked, particularly notable because of his attractiveness, like that of a young girl, a delicate, feminine beauty, but counterbalanced by his steady, calm, fierce, and focused glance, like that of a tiger: he was adored and he created dread" (Lost Illusions).

The contrast between the dandy's leisured pursuit of beauty and the soulless grind of the workingman's existence was stressed in Balzac's novels.

His ideology straddles the divide between latter nineteenth-century French and British conceptions of the Decadent Dandy and a British model of dandyism as a phenomenon situated in a particular social environment.

Charles Baudelaire and Joris-Karl Huysmans, among others, were impressed by him.

For them, the dandy represented a brave outsider struggling against increasing industrialization and social homogeneity.

Balzac developed his unique aesthetic and public presence.

He owed his tailor 904 francs by the end of 1830, which was more than his annual spending allowance for food and accommodation in Paris.

As a young, successful writer, he said that his unusual attire served as an advertisement and that his cane made Paris buzz.

Indeed, Balzac's accessories seem to have been especially noteworthy: he wore coat buttons that were intricately carved out of gold, carried a huge cane studded with turquoise, and modeled an astounding array of waistcoats and gloves.

Even though he tried to be elegant, he did not always have a good physique, and his flashy style was not always well-liked.

He was small and squat physically, and while focused on his task, he neglected to maintain personal cleanliness.

He had diamond bands on filthy fingers and flashing gems on soiled shirtfronts, according to Captain Gronow.

He often used renowned tailors, as well as haberdashers, glovemakers, and other tradespeople, as characters in his books.

It is said that he paid for his clothes by praising a few tailors in his literature, mentioning their names, addresses, and praise for their work.

For instance, the young provincial poet Lucien de Rubempré is humiliated when he spends cash on an ill-fitting, neon green ready-made suit and takes it to the Paris Opéra (Illusions Perdues, 1837–1843).

Henry de Marsay, a sophisticated dandy, disparages Lucien by likening him to a dressed mannequin.

The next day, he visits Staub, a tailor who worked for Balzac himself, and spends the majority of his annual salary on a new wardrobe.

He uses his new appearance to his advantage when he returns to his hometown of Angoulême.

All of the city's noblewomen are drawn to him because of his skin-tight black pants.

They come in droves to see him in his new persona as a dashing lion or a man of style.

Men continued to flaunt their bodies, much to the great dismay of the skinny or poorly built, and Lucien's figure was Apollonian, according to Balzac, who noted that the fashions of the day were best suited to sculptural physiques.

The Staub suit completely changes Lucien's life in Paris, propels him to overnight fame, and aids in the beginning of his writing career.

The social influence of appearance and behavior is celebrated in this book.

The early journalism of Honoré de Balzac devotes particular attention to men's attire.

The Traité de la vie élégante (Treatise on the Elegant Life), which was published in Émile de Girardin's royalist magazine La Mode between 2 October and 6 November 1830, is the most significant work directly linked to dandyism.

The British dandy George Brummell, referred to in this work as the "patriarch of fashion," is fictionalized.

Balzac employs him as a spokesperson to further his own ideas about tasteful attire and way of life.

He invented the term vestignomonie (vestignomony), a play on the hoax of physiognomy, in the Treatise.

Balzac asserted that clothes could be read and decoded in the same manner as face kinds and expressions, which physiognomists said might reveal human nature.

In democratic, post-revolutionary France, Balzac said that it was simple for the observer to distinguish between persons from different social classes and professions despite the appearance of growing uniformity in clothes.

He maintained that clothing betrayed the doctor, aristocrat, or student from the Marais, Faubourg Saint-Germain, Latin Quarter, or Chaussée d'Antin areas of Paris.

Balzac's later works show a continuing interest in vestimentary style, even if most of his early work was published in fashionable publications like La Mode, Le Voleur, and La Silhouette.

The ninety-odd volumes of La Comédie Humaine (The Human Comedy), which is a pun on Dante's Divine Comedy, place a significant emphasis on dress and attire.

A picture of French social life from the Revolution (1789) to the end of the July Monarchy may be seen in these works (1848).

Eugène de Rastignac, Lucien de Rubempré, Maxime de Trailles, Charles Grandet, Georges Marest, Amédée Soulas, Lousteau, Raphael Valentin, and Henry de Marsay are among the most significant dandy figures in his books.

His most significant books are Old Goriot, Cousin Bette, Eugénie Grandet, and Lost Illusions.

Balzac's meticulous observations and in-depth descriptions provide a realistic portrait of the subtleties of clothing in his day and signal the significance of fashion in realist fiction.

While French literary criticism recognizes Balzac's significance to the study of fashion, several of his significant journalistic works have not yet been translated into English.

The linguistic descriptions of clothing in his books, however, are among the most captivating and complex ever written.

Find Jai on Twitter | LinkedIn | Instagram

See also:

Fashion, Historical Studies of.

References And Further Reading:

Balzac, Honoré de. Lost Illusions (Illusions perdues). Translated by Herbert J. Hunt. Harmondsworth, U.K.: Penguin, 1971.

—. Traité de la vie élégante, suivi de théorie de la démarche. Paris: Arléa, 1998.

Boucher, François, and Philippe Bruneau. Le vêtement chez Balzac, Paris: extraits de la Comédie humaine l’Institut Français de la Mode, 2001.

Fortassier, Rose. Les ecrivains français et la mode. Paris: Puf, 1988.

Moers, Ellen. The Dandy: Brummell to Beerbohm. London: Secker and Warburg, 1960.

- Get link

- X

- Other Apps