Featured

- Get link

- X

- Other Apps

Beards and Mustaches

Beards and mustaches have deep and nuanced cultural implications since facial hair is closely linked to masculinity.

Growing a mustache or beard, or going without shaving, may communicate information about sexual orientation, religion, and other significant facets of cultural history.

Facial hair has historically served as a sign of affiliation with a tribe, ethnic group, or culture in many civilizations, denoting adoption of that group's cultural values and rejection of those of other groups.

A well-groomed beard was a sign of a philosopher in ancient Greece, but the Greeks also separated themselves from the barbaroi (literally, "barbarians," or "hairy ones") to their north and east.

This differentiation sometimes tolerated a certain ambiguity.

Although some important men in early imperial China, such as judges and military commanders, had beards, hairiness was often associated with the pastoral, "uncivilized," peoples of the northern border; by later imperial periods, the majority of Chinese men were clean-shaven.

"The hairy man was placed outside the bounds of the cultivated field, in the wilderness, the mountains, and the forests: the frontier of human civilization, he lingered on the verge of bestiality," writes Frank Dikotter.

Body hair was a sign of physical regression brought on by a lack of prepared food, correct attire, and right behavior.

On the other hand, beards were braided and trained to curl upward at the ends in ancient Egypt, where they were linked with great position.

Both male and female kings had fake beards that were made of gold.

Slaves had clean-shaven faces in the ancient Mesopotamian, Assyrian, Sumerian, and Hittite empires, whereas those of high social position wore beards that were curled and ornately ornamented.

Richard Corson examines the complexity of facial hair throughout history in his book Hair: The First Five Thousand Years, and he notes that in the ancient world, "during shaved eras, beards were permitted to grow as a gesture of grief."

Additionally, "slaves were compelled to wear beards as a symbol of their subordination" in the early first century, but as free men began to sport beards in the second and third centuries, slaves had to identify themselves as free by shaving their faces.

By the Middle Ages, long mustaches were once again a sign of aristocratic origin.

They were the standard among Goths, Saxons, and Gauls and were worn "falling down over their breasts like wings".

Many faiths have had issues with facial hair.

In 1073, Pope Gregory VII issued a papal order outlawing bearded clergy.

Beards are worn as a symbol of adherence to religious rules in Hasidic Jewish culture.

Some more conservatively devout Muslims who believe that growing a beard is a sign of cleanliness, submission to God, and masculine gender are quite critical of Muslim males who remove their facial hair.

Men have been required to wear untrimmed beards in several Muslim nations (such as Afghanistan under the Taliban).

However, in recent decades, the wearing or shaving of facial hair has tended to become more of a fashion statement than an issue of cultural identity in Western society.

For the majority of history, the ability of barbers and personal servants to sharpen razors and soften beards with hot water and emollients has been necessary for shaving facial hair and shaping mustaches and beards.

In 1770, Jean-Jacques Perret produced the first safety razor.

It was offered together with a manual for using it called La Pogotomie and comprised of a blade with a wooden guard (The Art of Self-Shaving).

The cutthroat razor was replaced by the T-shaped Gillette razor when it was created in 1855.

As the century went on, self-shaving gained popularity, particularly when Gillette significantly modified his initial invention in 1895 by introducing the disposable razor blade.

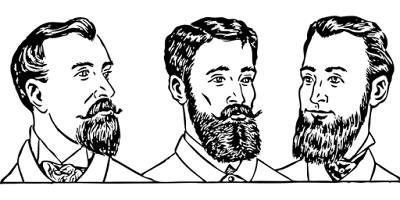

As facial hair replaced headgear as the main focus of male personal fashion in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, there have been a wide variety of beard and mustache styles.

Men may choose for muttonchops, which are named for their form, Piccadilly weepers, which are extremely long side-whiskers, Burnsides, which later developed into sideburns, or the short, pointed Vandyke beard, which alludes to a Renaissance Holland style.

Soup strainers are full mustaches that extend over the upper lip.

Small businesses emerged to produce and sell the many items that were created to assist groom and style facial hair, including tonics, waxes, and pomades.

Having fashionable mustaches and beards may make you feel good about yourself.

The moustaches are lovely, magnificent, Charles Dickens remarked of his own facial adornment.

To enhance their form, I have made them shorter and given them a little trimming at the ends (Corson 1965, p. 405).

Because of its historical ties to the military, facial hair was often seen as dashing and macho throughout parts of western Europe and America.

By the middle of the nineteenth century, medical professionals had warned men that going clean-shaven might be bad for their health.

For instance, it was suggested that bronchial issues might arise if a mustache and beard were not worn to filter the air going to the lungs.

Therefore, having a clean shave at the turn of the century was almost seen as a rebellious act by bohemians and artists like Aubrey Beardsley and playwright Oscar Wilde.

However, the clean-shaven look had become popular in mainstream fashion by the 1920s.

After then, having facial hair became a symbol of defiance or creative self-expression.

By the late 1920s, Salvador Dali had a highly detailed waxed mustache that signified his stature as an artist.

Military personnel continued to have mustaches, and names of styles like Guardsman, Major, and Captain reflect this.

By the middle of the 20th century, the beard had become uncommon, and young bohemians adopted it as a sign of nonconformity in the 1950s.

With the hippy movement in the late 1960s, beards continued to be a countercultural statement as many young men saw facial hair as a sign of "naturalness" or a display of respect for revolutionaries like Che Guevara and the leader of Cuba, Fidel Castro.

The beard was given a leather-clad hypermasculinity by bikers and Hells Angels.

Some segments of homosexual society also adopted bearded hypermasculinity.

By the 1970s, San Francisco's streets were filled with clones sporting tight trousers, short hair, and mustaches.

As shown by the actor Tom Selleck in the well-known television series Magnum P.I., this appearance has become mainstream.

As seen on the faces of the pop sensation George Michael and the actor Bruce Willis, designer stubble—an look created by going without shaving for a day or two—became the new standard for actors and male models by the middle of the 1980s, replacing full beards or mustaches.

As a consequence of the grunge movement coming out of Seattle and the New Age Traveler alliance in Europe, the 1990s saw a resurgence of beards and stubble.

Both organizations, one linked to rock music and the other to environmental activism, pushed for a restoration to "authenticity" and discouraged regular shaving.

Kurt Cobain, lead vocalist of the band Nirvana, had short beards and stubble.

In opposition to environmental degradation, Swampy, a well-known British environmental activist, donned a full head of dreadlocks and a matching "natural" beard.

The goatee and love bud are the two variations of facial hair that are most popular nowadays (in which a small patch of beard is allowed to grow below the lower lip).

Men of succeeding generations, the majority of whom are clean-shaven, have largely rejected the full beard with side-whiskers, which is now mostly seen on the faces of men who were young in the 1950s and 1960s.

Find Jai on Twitter | LinkedIn | Instagram

See also:

Fashion and Identity; Hairstyles.

References And Further Reading:

Corson, Richard. Hair: The First Five Thousand Years. London: Peter Owen, 1965.

Dikotter, Frank. “Hairy Barbarian, Furry Primates, and Wild Men: Medical Science and Cultural Representations of Hair in China.” In Hair: Its Power and Meaning in Asian Cultures. Edited by Alf Hiltebeitel and Barbara D. Miller. Albany: State University of New York Press, 1998.

Peterkin, Allan. One Thousand Beards: A Cultural History of Facial Hair. Vancouver, Canada: Arsenal Pulp Press, 2001.

- Get link

- X

- Other Apps